A lot of things have happened in my life, by which I mean partly in my environment and, mostly, in my mind. As I do not yet know how to meditate — though that has been on the short list of things I’d like to learn for quite a while now — my mind is a cluttered, unquiet place most of the time.

One weekend, a year or so ago, my husband and children were out of the house, so I took my hearing aids out and sat on the floor of my bedroom for hours and let my thoughts come. I wrote each thought, or a word or two that would later remind me of its gist, onto a separate colored sticky note, which I then put up on the wall and organized and analyzed until the kids got home. When I told a friend about this exercise, she said, “That’s so you.” So I guess one thing that has happened in my life, that is, in my environment, that is, in the minds of some of the people around me, is that I’ve developed a bit of a reputation for doing things like that.

I think the exercise was ostensibly about goal-setting. I frankly don’t remember anymore. What I do remember is that my thoughts seemed to be distributed in equal parts in these categories: chores I needed to remember to do later (or, rather, remembered but needed to motivate myself to do); work; hopes for my children; insecurities about how little I give back to my various communities; and ideas for stories, screenplays and novels.

I am keenly aware that my experiencing self juggles far too many things in pursuit of a full life or some other such nonsense, while my narrating self cries softly — and perhaps unsurprisingly, given that it is a narrator — almost daily, calling out to me to put down all those balls and pick up a pen and write.

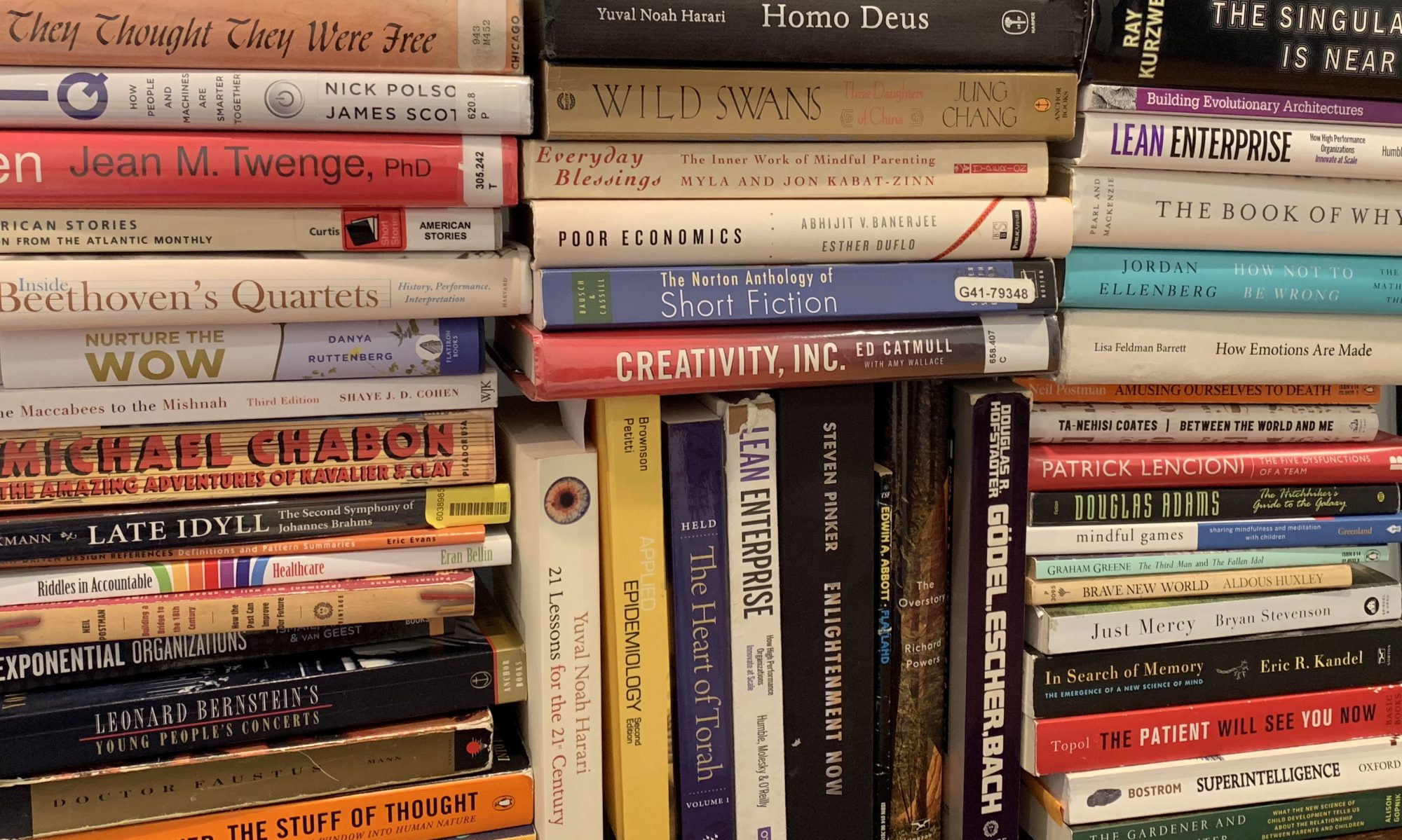

I blame Yuval Noah Harari for the question that preoccupies me and fuels most of my ideas for writing projects. At the end of the last chapter of his book, Sapiens, after a discussion of the possibilities of biotechnology, he writes, “Since we might soon be able to engineer our desires, too, perhaps the question facing us is not ‘What do we want to become?’ but ‘What do we want to want?’” And then, like a television writer desperate to renew, promising to resolve the question in the next season — which he did not do, by the way, in either of his subsequent books — he writes, “Those who are not spooked by this question probably haven’t given it enough thought.”

Thanks, Yuval. You precipitated the closest thing to a mental health crisis I have ever experienced. I think, though I am no psychologist, that this means that I am, knock on wood, relatively healthy in the mental department, all things considered. For this I am eternally grateful and do not mean to minimize the agony of others or compare my intellectual suffering to the true suffering of others. Mental health is, after all, pretty much all there is.

But in any event, reading that line in Sapiens was a bit, well, a tad bit destabilizing. You can ask my husband; I became pretty insufferable at dinner parties, always bringing it up to see if someone had some deep reading of scripture or tea leaves or current events or even social media (my desperation knew no bounds). I sought an answer that could direct further goal-setting exercises and help my narrating self advance my plot.

I thought for a minute there, a few months back, that I had the answer. I was sitting in a colleague’s office at work waiting for a meeting to begin when I saw the book on a shelf and reached for it, maybe to see if the quote was still there. Years had passed since it had infected my mind, and I had learned to live without an answer, or maybe with the sense that the question itself was the answer. I found that I hadn’t quite remembered the words exactly, and I showed it to a colleague who was sitting and waiting with me, mainly to pass the time. I told him how the question had for a while consumed me in an unhealthy way. “What do we want to want?” How it has basically become my mantra. “What do we want to want?” he asked, thinking for just a moment. “Why, as little as possible, I guess.”

That quieted my mind for, like, a minute or two.

But then Bill Gates cracked it wide open again. Bill and Melinda. I made the mistake of reading their foundation’s fact sheet, which states that, “Guided by the belief that every life has equal value, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation works to help all people lead healthy, productive lives.” This echos the aspect of Judaism that most powerfully speaks to me — calls to me — to be a force for good in the world. From the margins of my high holidays prayerbook, Mordecai Kaplan asks me every year, “Shall we not give of our store to the relief of suffering, the healing of sickness, the dispelling of ignorance an error, the righting of wrongs and the strengthening of faith?” I want far too much to want as little as possible.

I want to be a part of the story in which all people lead healthy, productive lives. I want to live by Rabbi Hillel’s rule, “Do not do unto others that which is unpleasant to you,” and I want to be called to take this to the next level, too — to end suffering where we can and then, if possible, transform suffering into flourishing. This is what I want to want. Easy peasy. Well, maybe not, but at least it’s nice to know which way you’re going, because, if you don’t, so says the Cheshire Cat, it doesn’t much much matter which way you go.

So, thank you, Bill and Melinda. Thank you, Rabbis Hillel and Kaplan. Thank you Lewis Carroll, and even you, Yuval. Thank you all for giving me my north star, my beacon of freedom from a life of “as little as possible,” which is a noble pursuit but was just never going to work for me. I want too much. Now that I know where I’m going, I will attempt to write myself there. Harold and his purple crayon come to mind.

Apparently, the Dali Lama never said, “Be the change you want to see in the world.” Maybe the person who did say it thought it would gather more steam if attributed to His Holiness. Fine. Whatever works. And I’m okay if my new, slightly tweaked version of that meme spreads no further than the faded sticky note on my bedroom wall because it has already served its purpose in guiding me — to be the story I want to write in the world.